1. Biological and cultural evolution: from Homo habilis (or earlier) to Homo sapiens sapiens in the fossil record

2. Cultural and sociopolitical evolution: from hunting and gathering to the agricultural, industrial, and post-industrial revolutions

a. The Neolithic Revolution

b. Early civilization and the rise of the state

c. Democratization

c. Democratization

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Homo sapiens– After Homo erectus came, the Homo sapiens who separated into two types:

1) Homo sapiens neanderthelensis

They had a brain size larger than modern man and were gigantic in size. Also, they had a large head and jaw and were very powerful and muscular. They were carnivores and the tools from the era indicate they were hunters. They were also caving dwellers but their caves were more comfortable and they lived in groups and hunted for food gathering.

2) Homo sapiens sapiens

Also known as ‘modern-day man’ is what we are today. Compared to the Homo sapiens neanderthelensis, they became smaller in size and the brain size reduced to 1300cc. There was also a reduction in the size of the jaw, rounding of the skull and chin. Cro- Magnon was the earliest of the Homo sapiens. They spread wider from Europe, Australia, and the Americas. They were omnivores, had skillful hands, developed the power of thinking, producing art, more sophisticated tools and sentiments.

Evolution is not a thing of the past and is continuing even now. Humans are undergoing ‘natural selection’ for many different traits based on their life and environment in the present. It is believed that the jaw size is reducing further and the wisdom teeth are soon going to become extinct.

The Neolithic Revolution

Neolithic Age

The Neolithic Age is sometimes called the New Stone Age. Neolithic humans used stone tools like their earlier Stone Age ancestors, who eked out a marginal existence in small bands of hunter-gatherers during the last Ice Age.

Australian archaeologist V. Gordon Childe coined the term Neolithic Revolution in 1935 to describe the radical and important period of change in which humans began cultivating plants, breeding animals for food and forming permanent settlements. The advent of agriculture separated Neolithic people from their Paleolithic ancestors.

Many facets of modern civilization can be traced to this moment in history when people started living together in communities.

Causes Of The Neolithic Revolution

There was no single factor that led humans to begin farming roughly 12,000 years ago. The causes of the Neolithic Revolution may have varied from region to region.

The Earth entered a warming trend around 14,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age. Some scientists theorize that climate changes drove the Agricultural Revolution.

In the Fertile Crescent, bounded on the west by the Mediterranean Sea and on the east by the Persian Gulf, wild wheat and barley began to grow as it got warmer. Pre-neolithic people called Natufians started building permanent houses in the region.

Other scientists suggest that intellectual advances in the human brain may have caused people to settle down. Religious artifacts and artistic imagery—progenitors of human civilization—have been uncovered at the earliest Neolithic settlements.

The Neolithic Era began when some groups of humans gave up the nomadic lifestyle completely to begin farming. It may have taken humans hundreds or even thousands of years to transition fully from a lifestyle of gathering wild plants to keeping small gardens and later tending large crop fields.

Neolithic Humans

The archaeological site of Çatalhöyük in southern Turkey is one of the best-preserved Neolithic settlements. Studying Çatalhöyük has given researchers a better understanding of the transition from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering to an agriculture lifestyle.

Archaeologists have unearthed more than a dozen mud-brick dwellings at the 9,500 year-old Çatalhöyük. They estimate that as many as 8,000 people may have lived here at one time. The houses were clustered so closely back to back, that residents had to enter the homes through a hole in the roof.

Plant domestication: Cereals such as emmer wheat, einkorn wheat and barley were among the first crops domesticated by Neolithic farming communities in the Fertile Crescent. These early farmers also domesticated lentils, chickpeas, peas and flax.

Domestication is the process by which farmers select for desirable traits by breeding successive generations of a plant or animal. Over time, a domestic species becomes different from its wild relative.

Neolithic farmers selected for crops that harvested easily. Wild wheat, for instance, falls to the ground and shatters when it is ripe. Early humans bred for wheat that stayed on the stem for easier harvesting.

Around the same time that farmers were beginning to sow wheat in the Fertile Crescent, people in Asia started to grow rice and millet. Scientists have discovered archaeological remnants of Stone Age rice paddies in Chinese swamps dating back at least 7,700 years.

In Mexico, squash cultivation began about 10,000 years ago, while maize-like crops emerged around 9,000 years ago.

Livestock: The first livestock were domesticated from animals that Neolithic humans hunted for meat. Domestic pigs were bred from wild boars, for instance, while goats came from the Persian ibex.

The first farm animals also included sheep and cattle. These originated in Mesopotamia between 10,000 and 13,000 years ago. Water buffalo and yak were domesticated shortly after in China, India and Tibet.

Early civilization and the rise of the state

What do civilizations have in common?

Cities were at the center of all early civilizations. People from surrounding areas came to cities to live, work, and trade. This meant that large populations of individuals who did not know each other lived and interacted with one another. So, shared institutions, such as government, religion, and language helped create a sense of unity and also led to more specialized roles, such as bureaucrats, priests, and scribes.

Cities concentrated political, religious, and social institutions that were previously spread across many smaller, separate communities, which contributed to the development of states. start superscript, 5, end superscript

A state is an organized community that lives under a single political structure. A present-day country is a state in this sense, for example. Many civilizations either grew alongside a state or included several states. The political structures that states provided were an important factor in the rise of civilizations because they made it possible to mobilize large amounts of resources and labor and also tied larger communities together by connecting them under a common political system.

Early civilizations were often unified by religion—a system of beliefs and behaviors that deal with the meaning of existence. As more and more people shared the same set of beliefs and practices, people who did not know each other could find common ground and build mutual trust and respect.

It was typical for politics and religion to be strongly connected. In some cases, political leaders also acted as religious leaders. In other cases, religious leaders were different from the political rulers but still worked to justify and support the power of the political leaders. In Ancient Egypt, for example, the kings—later called pharaohs—practiced divine kingship, claiming to be representatives, or even human incarnations, of gods.

Both political and religious organizations helped to create and reinforce social hierarchies, which are clear distinctions in status between individual people and between different groups. Political leaders could make decisions that impacted entire societies, such as whether to go to war. Religious leaders gained special status since they alone could communicate between a society and its god or gods.

In addition to these leaders, there were also artisans who provided goods and services, and merchants who engaged in the trade of these goods. There were also lower classes of laborers who performed less specialized work, and in some cases there were slaves. All of these classes added to the complexity and economic production of a city.

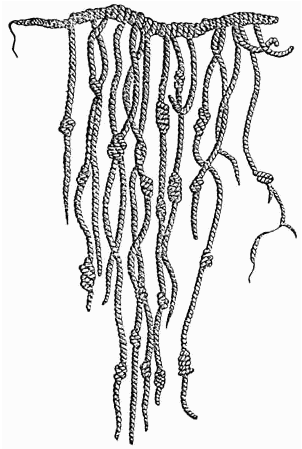

Writing emerged in many early civilizations as a way to keep records and better manage complex institutions. Cuneiform writing in early Mesopotamia was first used to keep track of economic exchanges. Oracle bone inscriptions in Ancient China seem to have been tied to efforts to predict the future and may have had spiritual associations. Quipu—knotted strings used to keep records and perform calculations—appeared in South America. In all the places where writing developed—no matter its form or purpose—literacy, or the ability to read and write, was limited to small groups of highly educated elites, such as scribes and priests.

Writing offered new methods for maintaining law and order, as well. The first legal codes, or written collections of laws, were the Code of Ur-Nammu from Sumer, written around 2100 to 2050 BCE and the Code of Hammurabi from Babylon, written around 1760 BCE. The benefit of written laws was that they created consistency in the legal system.

This shift toward writing down more information might not seem like a significant development, especially since most people were unable to read or write. However, having consistent, shared records, laws, and literature helped to strengthen ties between increasingly large groups. start superscript, 6, end superscript

Another notable feature of many civilizations was monumental architecture. This type of architecture was often created for political reasons, religious purposes, or for the public good. The pyramids of Egypt, for example, were monuments to deceased rulers. The ziggurats of Mesopotamia and the pyramids of early American societies were platforms for temples. Defensive walls and sewer systems provided defense and sanitation, respectively. start superscript, 7, end superscriptAlthough a few examples of monumental architecture from pre-agricultural societies exist, the greater organization and resources that came with civilization made it much easier to build large structures.

There were many features that early civilizations had in common. Most civilizations developed from agrarian communities that provided enough food to support cities. Cities intensified social hierarchies based on gender, wealth, and division of labor. Some developed powerful states and armies, which could only be maintained through taxes.

Civilization is a tricky concept for many reasons. For one thing, it can be difficult to define what counts as a civilization and what does not, since experts don’t all agree which conditions make up a civilization. For example, people living in the Niger River Valley in West Africa achieved an agricultural surplus, urbanization, and some specialization of labor, but they never developed strong social hierarchies, political structures, or written language—so scholars disagree on whether to classify it as a civilization. Also, due to extensive cultural exchange and diffusion of technology, it can be difficult to draw a line where one civilization ends and another begins.

0 comments:

Post a Comment